I have a friend who was a member of a special forces unit of the Navy during the Vietnam War. I call it a war rather than a conflict because what else could you call it if he lived outside, slept in foxholes, fought battles in the jungle, watched many a fellow soldier die and killed more Viet Cong than he could count?

It was definitely a war.

My friend will tell some stories, but does not wish to share any gory details. He is a great guy, not doing so well these days physically as he is seventy-two years old and suffers from numerous health problems, yet he remains the toughest guy that I know. He has nine medals in a case and receives two monthly pension payments for his efforts in Vietnam. He also collects two additional pension payments, one from the Carpenter’s union, which he spent about twenty years in as a foreman after the war, and another from IMRF, Illinois’ municipal pension system that I currently contribute to and which he contributed to for twenty-five years. I met him at my current place of work and we became very close following a rough start to our relationship, but in the spirit of forgiveness and wanting to get along, I let bygones be bygones.

I should add that he and his wife raised not six, not seven or even eight, but nine children. Six are biologically theirs and three were adopted from my friend's wife's sister who was incapable of raising her own three children for reasons unknown to me and none of my business. I have heard a lot about his children and grandchildren but have never met any of them.

He is also a millionaire several times over, but one could not really replicate how he did it anymore. You would have to be a combination of Rich Dad Robert Kiyosaki's property buying prowess, a property inheritance from an Italian family in the New York grocery business and investing as steadily in low-cost index funds as John Bogle, himself. Not to mention a successful side career as a gambler.

My other retired friend, a pastor who I also met at my current place of work, and my soldier friend will be meeting for lunch in two weeks, on March 9th. My pastor friend and I will most likely each order salads, and our mutual soldier friend will only drink a small coffee since he can no longer eat most foods. He is not dying, but he is not in great shape either.

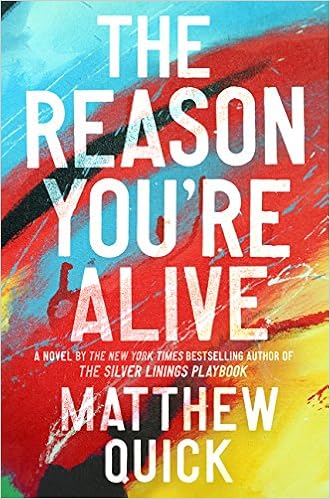

I mention my retired friend because I recently read a book whose main character reminded me quite a bit of him. The book was great and is titled The Reason You're Alive by Matthew Quick.

Although I read about a hundred self-help and financial books in a row, having shifted from reading nothing but fiction for many years to reading nothing but How to Change Your Way of Thinking/Become Wealthier/How to Become More Successful books for most of 2016 and 2017, I have read about ten works of fiction since the beginning of this year.

I still read self-help and finance books, but not quite as many as before. As difficult as it is for me, I now often read two or more books concurrently, going back and forth from one to another depending on my mood. Right now, I am in the middle of three books.

Although the title of my blog and Twitter handle as the Money Mensch, financial items and thoughts are just one part of my life, although a rather large part considering that a few hours do not go by that I do not at least think about money for at least a little while.

Ironically, some of the best advice that I read of late was from the point of view of David Granger, the protagonist in Quick’s novel. After sixty-eight-year-old Granger crashes his BMW, medical tests reveal a brain tumor that he readily attributes to his wartime Agent Orange exposure. He wakes up from surgery repeating a name no one in his civilian life has ever heard—that of a Native American soldier whom he was once ordered to discipline. David decides to return something precious he long ago stole from the man he now calls Clayton Fire Bear.

The novel goes from there and we follow along as the opinionated and goodhearted American patriot fights like hell to stay true to his red, white, and blue heart, even as the country he loves rapidly changes in ways he doesn’t always like or understand.

The inspirational words are given as the narrator explains that, despite his cursing, fighting and politically incorrect way of doing things, he became a highly successful millionaire banker in the years following his return stateside.

“When you have watched your friends die in your arms, felt the flesh rot off your feet, and gone nose to nose with pure evil, going the extra mile with an investor – laughing at his dumb jokes, having that extra late-night drink when you’d much rather be home with your family, and sniping the in-house competition by inserting the right word at the right time into the boss’s ear - it’s like R&R in Hawaii compared to wartime Vietnam.”

Wow! I began to view my own stress and anxiety in a slightly different light after reading that passage.

The narrator continues, “I used to just laugh when my fellow bankers complained about their imaginary stress. I was the apex predator in any jungle or boardroom, and I made sure everyone was damn sure aware of that fact…People in power take care of the apex predator. Always. Doesn’t matter if we are wearing suits or camouflage. The rules are the same.”

I make no claim as being the apex predator in a room. As a matter of fact, my new boss’s bumbling, dumb but aggressively and loudly stated questions and statements somehow led to his being rapidly promoted through our bureaucracy. He is far from an apex predator, but his size and aggressive manner tend to make sure that the powers that be take care of him always, as the above quote attests to.

Reading the fictional account of how Granger rose in the banking industry after taking out dozens of Viet Cong for weeks in the jungle with a bloodthirsty Cambodian partner named Tao, I must concede that my own worries pale in comparison with something like that.

In the book, which I suggested that my wife read even though she may be offended by the narrator’s blunt description of gays, Blacks, Asians and other minorities, the narrator is sent to a psychiatrist following his MIA days in the jungle. She suggests that both the killing spree and his partner in crime were just figments of his imagination, attributable to the stressful situation that he was in, not wanting to consider that his story was true.

The story reminded me of my friend’s account of being MIA with three other soldiers for three months, detached from the rest of their unit in a major battle where only a handful lived to tell of it. When they finally reconnected with other Americans, they were well over one hundred miles away from where they had been ambushed and had been living off of the foliage for ninety days, killing anyone or anything that moved. The four of them had lost most of their body weight.

He has never given me an approximation, nor would I ask, but he has told me more than once that he and his two other buddies from New York who he was stranded with lived by their wits like animals in the jungle, just trying to survive. One of the four was horribly injured and could not walk at all, and the biggest of the three remaining soldiers carried him the entire way for weeks on end. Talk about owing someone your life!

I told my friend that he should record his experiences with Story Corps, but his reply is that he didn’t know why the fuck they were sent there in the first place, he was happy as hell to get the fuck out of there after an eighteen month tour, and he never wants to think about it again but is okay with collecting the pension payments.

I can’t say that I would feel any differently.

But the next time that I am feeling a high amount of stress and anxiety, like I was today at about 10:30 a.m. when I simultaneously had my boss, a local business person, a sales person and a broker looking for me at the very same time, I should remember what true stress is.

Compared to what my buddy went through fifty years ago in the jungles of Vietnam, dealing with a young boss walking in while two people are calling me and another person is dropping in is like a vacation in Hawaii.

My friend will tell some stories, but does not wish to share any gory details. He is a great guy, not doing so well these days physically as he is seventy-two years old and suffers from numerous health problems, yet he remains the toughest guy that I know. He has nine medals in a case and receives two monthly pension payments for his efforts in Vietnam. He also collects two additional pension payments, one from the Carpenter’s union, which he spent about twenty years in as a foreman after the war, and another from IMRF, Illinois’ municipal pension system that I currently contribute to and which he contributed to for twenty-five years. I met him at my current place of work and we became very close following a rough start to our relationship, but in the spirit of forgiveness and wanting to get along, I let bygones be bygones.

I should add that he and his wife raised not six, not seven or even eight, but nine children. Six are biologically theirs and three were adopted from my friend's wife's sister who was incapable of raising her own three children for reasons unknown to me and none of my business. I have heard a lot about his children and grandchildren but have never met any of them.

He is also a millionaire several times over, but one could not really replicate how he did it anymore. You would have to be a combination of Rich Dad Robert Kiyosaki's property buying prowess, a property inheritance from an Italian family in the New York grocery business and investing as steadily in low-cost index funds as John Bogle, himself. Not to mention a successful side career as a gambler.

My other retired friend, a pastor who I also met at my current place of work, and my soldier friend will be meeting for lunch in two weeks, on March 9th. My pastor friend and I will most likely each order salads, and our mutual soldier friend will only drink a small coffee since he can no longer eat most foods. He is not dying, but he is not in great shape either.

|

Although I read about a hundred self-help and financial books in a row, having shifted from reading nothing but fiction for many years to reading nothing but How to Change Your Way of Thinking/Become Wealthier/How to Become More Successful books for most of 2016 and 2017, I have read about ten works of fiction since the beginning of this year.

I still read self-help and finance books, but not quite as many as before. As difficult as it is for me, I now often read two or more books concurrently, going back and forth from one to another depending on my mood. Right now, I am in the middle of three books.

Although the title of my blog and Twitter handle as the Money Mensch, financial items and thoughts are just one part of my life, although a rather large part considering that a few hours do not go by that I do not at least think about money for at least a little while.

Ironically, some of the best advice that I read of late was from the point of view of David Granger, the protagonist in Quick’s novel. After sixty-eight-year-old Granger crashes his BMW, medical tests reveal a brain tumor that he readily attributes to his wartime Agent Orange exposure. He wakes up from surgery repeating a name no one in his civilian life has ever heard—that of a Native American soldier whom he was once ordered to discipline. David decides to return something precious he long ago stole from the man he now calls Clayton Fire Bear.

The novel goes from there and we follow along as the opinionated and goodhearted American patriot fights like hell to stay true to his red, white, and blue heart, even as the country he loves rapidly changes in ways he doesn’t always like or understand.

The inspirational words are given as the narrator explains that, despite his cursing, fighting and politically incorrect way of doing things, he became a highly successful millionaire banker in the years following his return stateside.

“When you have watched your friends die in your arms, felt the flesh rot off your feet, and gone nose to nose with pure evil, going the extra mile with an investor – laughing at his dumb jokes, having that extra late-night drink when you’d much rather be home with your family, and sniping the in-house competition by inserting the right word at the right time into the boss’s ear - it’s like R&R in Hawaii compared to wartime Vietnam.”

Wow! I began to view my own stress and anxiety in a slightly different light after reading that passage.

The narrator continues, “I used to just laugh when my fellow bankers complained about their imaginary stress. I was the apex predator in any jungle or boardroom, and I made sure everyone was damn sure aware of that fact…People in power take care of the apex predator. Always. Doesn’t matter if we are wearing suits or camouflage. The rules are the same.”

I make no claim as being the apex predator in a room. As a matter of fact, my new boss’s bumbling, dumb but aggressively and loudly stated questions and statements somehow led to his being rapidly promoted through our bureaucracy. He is far from an apex predator, but his size and aggressive manner tend to make sure that the powers that be take care of him always, as the above quote attests to.

Reading the fictional account of how Granger rose in the banking industry after taking out dozens of Viet Cong for weeks in the jungle with a bloodthirsty Cambodian partner named Tao, I must concede that my own worries pale in comparison with something like that.

In the book, which I suggested that my wife read even though she may be offended by the narrator’s blunt description of gays, Blacks, Asians and other minorities, the narrator is sent to a psychiatrist following his MIA days in the jungle. She suggests that both the killing spree and his partner in crime were just figments of his imagination, attributable to the stressful situation that he was in, not wanting to consider that his story was true.

The story reminded me of my friend’s account of being MIA with three other soldiers for three months, detached from the rest of their unit in a major battle where only a handful lived to tell of it. When they finally reconnected with other Americans, they were well over one hundred miles away from where they had been ambushed and had been living off of the foliage for ninety days, killing anyone or anything that moved. The four of them had lost most of their body weight.

He has never given me an approximation, nor would I ask, but he has told me more than once that he and his two other buddies from New York who he was stranded with lived by their wits like animals in the jungle, just trying to survive. One of the four was horribly injured and could not walk at all, and the biggest of the three remaining soldiers carried him the entire way for weeks on end. Talk about owing someone your life!

I told my friend that he should record his experiences with Story Corps, but his reply is that he didn’t know why the fuck they were sent there in the first place, he was happy as hell to get the fuck out of there after an eighteen month tour, and he never wants to think about it again but is okay with collecting the pension payments.

I can’t say that I would feel any differently.

But the next time that I am feeling a high amount of stress and anxiety, like I was today at about 10:30 a.m. when I simultaneously had my boss, a local business person, a sales person and a broker looking for me at the very same time, I should remember what true stress is.

Compared to what my buddy went through fifty years ago in the jungles of Vietnam, dealing with a young boss walking in while two people are calling me and another person is dropping in is like a vacation in Hawaii.

Comments

Post a Comment