This Money Mensch worries about money. A lot.

|

Sometimes, that is how much a month of our middle class suburban lifestyle costs, with appliance replacement, auto repairs, tuition payments, dental visits, a check to the IRS and the like making it cost more and more.

Inasmuch as I am trying to improve my family's and my own lot in this life, I read about money frequently including ways of making more. Like writing blogs with ads scrolling through them. Like creating podcasts or creating subscription services or creating eBooks.

I am a very avid reader, typically reading a few hours per day, sometimes less.

Although I am coming off of two extremely busy weeks of working and traveling, I found the time to read Mind over Money: The Psychology of Money and How to Use It Better

Unlike many of the books that I read, learn from, and share about, this one was published fairly recently. It does not make it any better than the other books that I have read on the topic, just more recently written. Truth be told, it is one of the poorer books on the topic that I have read.

Since neither Ms. Hammond nor anybody else has ever paid me for a book review, I would give this book one star, perhaps one and a half.

Pocket Money

Hammond writes of the importance for kids to have some pocket money. As both a long-time recipient of and payer of weekly allowance, this is something that I firmly believe in.

| Source: Dreamtime.com |

She cites a study that showed that middle-income parents were more likely to make their children work for their allowance, an interesting finding considering that these parents could afford to be more generous without expecting any help around the house in return.

Hammond cites many studies and ideas on the topic, but concludes that what parents need to do is be open and consistent about where pocket money comes from and what children can expect to get.

He Makes More Than Me

Being a Brit, Hammond writes about some people that she knows in the financial sector in London.

She writes that a friend of hers in the financial sector described that even though he is making 300,000 pounds per year, he is jealous of someone else doing the same thing and making 400,000. It makes him feel undervalued.

Me, I would be dancing a jig if I could make $300,000 per. It would actually prompt me to upgrade my home, vehicles, TVs, phones and the like to match that much higher income. Plus, a British pound equals 1.29 U.S. dollars as of this writing, so 300,000 £ is actually like making about $400,000. Not too shabby, also considering that the people who she writes about are in their twenties to early thirties.

It got me thinking about a good friend of mine, who ended up getting a great job about five years ago. He and I were the two finalists for a major economic development position and, even though I really like the guy, they made what I still feel is the wrong decision and hired him over Yours Truly.

Since we are both employees of local government entities whose salaries are published online for the whole world to see, I reluctantly looked up his salary.

My friend is making $137,000, nearly $30,000 more than me!

Our skills are the same, I am perhaps a little bit more educated, and I have him by spades in the personality department.

Does it piss me off? You bet it does!

I understand that my best friend makes quite a bit more than I do. He is a mid-level IT guy for the State's largest insurance company, so it makes sense even though he gets to work remotely several times per week.

I understand it when they pay him a base salary around $125,000 or so and then give him a bonus in the $25,000 range around Christmas every year.

Do I regret not having gone into IT? You bet. Do I tell him that I am jealous of his job and that he works mainly with computers rather than people? You bet. Am I jealous of his large Christmas bonus, that he uses every winter break to take his wife and son somewhere exotic? Absolutely.

But when I hear of someone with the same skill set that I have doing the same thing that I do, but making $30,000 more, enough to cover my son's college tuition, and my daughter's in a few years, or enough to cover payments on a new car, repairs to our home and several nice vacations per year, you can bet that I am jealous.

Will I tell him that when I next see him? That you can bet I will not do.

Your Necessities Or Mine?

Hammond writes that we need money for life's necessities and that we can all agree on that. But what constitutes a necessity? That is what we are less likely to agree on.

What may be a necessity for you, like your gym membership or subscription to Netflix, is not a necessity for me at all.

What may be a necessity for me, like paying our son's college tuition or saving for our daughter's college, may not be one for you.

Smart phones are viewed as essential in many parts of the world today. Although my family utilizes pay-as-we-go phones, like families in lower income brackets than ours typically would, they are still smart phones and we seem to be using up the minutes and memory faster and faster every month.

Even though over ten grand leaves my wife's and my checking account most months, I would contend that we spent the vast majority of it on what we consider necessities - paying taxes, fixing our family car, getting one of my teeth fixed, purchasing new appliances, paying for education and activities for our children, food, shelter, pet-related items and many other typical middle income expenditures.

I know people who consider new car purchases, country club membership and European vacations to be necessities of life. To me, any of those would definite be luxury items, but to many struggling families, they might consider the new outfits and shoes that my wife purchased for our daughter last month to be luxuries, our new awesome $700 top-loading clothes washer that jiggles around and measures the load rather than just a plain old washer, and paying private college tuition to be luxuries that they can only dream of rather than necessities, like we consider them.

Twelve Attitude Categories

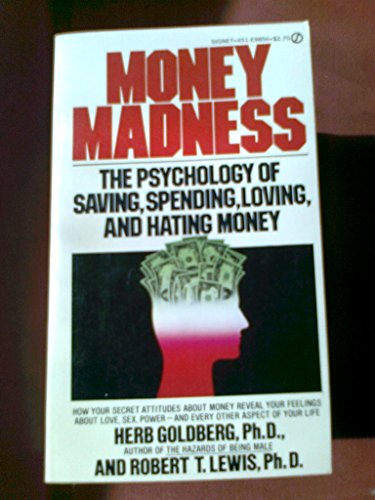

Hammond describes the often-cited 1978 book Money Madness,, the Psychology of Saving Spending Loving and Hating Money

|

I see several, but not all, of the traits in myself, as many people would. I am not nearly wealthy enough to fit into some of the categories, like the manipulator, empire builder, love buyer or godfather. Nor am I a compulsive bargain-hunter or love stealer.

If anything, I sometimes feel like a compulsive saver, especially when it comes to reaching my goal of saving $100,000 for each of my children for college, and I also sometimes feel like a self-denier, feeling guilty if I spend any money on myself and often spending any extra income on anyone except for myself. But is that really so bad, spending on our two children rather than new things for myself?

I do not think so.

Goldberg and Lewis characterize self-deniers as also pessimistic about the future and not daring to spend any money that they do not need to. I do not believe that I am that frugal. My lovely wife reminds me to spend for things like family trips and dinners out together and we spend a lot on things like attending concerts, horse riding and private music lessons for our daughter and our biggest expense, covering about $2,500 per month for tuition, room and board for our son, who is in his second semester of his sophomore year at a private college studying music.

Materialism

Hammond writes about how people's notions pertaining to money relate to materialism, which is often defined as the desire for material goods and money to the neglect of other things.

For a long time, materialism was considered to be a personality trait that stuck with you throughout life.

She cites the Belk Materialism Scale, which I then researched and read several abstracts and articles about including an article by Russell Belk of the University of Utah, himself, in 1984.

The three measures of materialistic traits as proposed, measured, and tested by Belk include: possessiveness, non-generosity, and envy.

Materialism tends to conjure a morally negative space and most of us would not want to admit to being materialistic. We do not wish to be led into buying more and more like the advertisers and the businesses that provide those goods and services want us to.

Hammond cites others who explain that materialism is not all bad, but there is a good kind and a bad kind. The good kind, known as instrumental materialism, is using material things to fulfill your personal values and goals. The bad kind, or terminal materialism, is where you use your money and material possessions to improve your own social status and generate envy in others.

The Poor and Their Payday Loans

If I loaned you $500, would you pay me back $550 when you get paid in two weeks? I would sure go for that, but I would rather have you pay me $1,100 in three or four weeks if I loaned you $1,000 today.

Those are the types of usurious rates that those with very little money sometimes borrow at, thus compounding their relative poverty.

People who resort to them seem to be displaying a condition that psychologists refer to as tunneling, where the mind's focus narrows. They just want to get their hands on some cash to meet their immediate needs, no matter how high the interest is.

| Source: creditcardchaser.com |

Struggling to make ends meet from day-to-day, month-to-month and year-by-year takes an enormous toll. This may be the explanation why poor people sometimes resort to ill-advised decisions such as these short-term loans at extortionate rates that the mafia would be ashamed to charge.

Hammond poses the notion that poor people may not be acting out of foolishness or fecklessness, but because their high stress levels affect the prefrontal cortex, perhaps they are less able to take the future into account.

Speaking of the Future...

In Chapter 13, For A Rainy Day, Hammond writes about something that I have read and written about a lot lately and will be explored somewhat more in depth in an upcoming post.

That is the notion that many of us find saving very difficult. We can save for short-term things like a new car, an outfit or vacation or other things that are just a few months away.

By contrast, it is difficult to save for unforeseen circumstances, old age or illness. We know that it is sensible and important, but it is a long time off and might not even ever happen. It also does not promise much in the way of pleasure, like a family vacation would over the summer and winter break, or a replacement for my 19-year-old beater Subaru would be.

Here in 2018, there are a lot more pressing current wants and needs. Saving an extra $600 this month for my wife and I to use in the 30's, assuming that we both make it, does not seem as exciting.

| Source: Enjoycompare.com |

As with money management, the idea is the same. When an unforeseen crisis hits, will you be ready for it? We may embrace living in the moment, living hand to mouth with our monthly salary, but what happens when a bad patch hits and you need money urgently?

There lies the wisdom of the adage – Saving For a Rainy Day.

Comments

Post a Comment